No Place to Dream

"Canada will soon be a society of have and have-nots," says Jerome, sipping a matcha drink, "and I want my kids to be among the haves."

We're at a Taiwanese cafe in North York, located in a strip mall that's grudgingly gentrifying. It's a neighbourhood for single-family homes, and according to the 2016 census, the average household income is $146,000. Middle-class almost, except when you look at the price of homes. At $2M, even a well-paid family doctor cannot afford the average home. Where does that leave a school teacher or a police constable?

This diminishment of opportunity, the sequestering of life's essentials for only the already-wealthy, the seeking of rent from an underclass fenced off from asset ownership - these were the defining attributes of feudal societies, their rigid class structures designed to grow wealth for the rich by extracting from the class below.

For Jerome, the price tag of placing his kids on the right side of the social divide was a $2.7M home in Markham. A precious number he was able to afford, not because he's a tech executive in the top 2% of Canadian income earners (he is), but because he bought his first home in the early 2000s when Canada was a better country for young people.

As I sat there, listening to Jerome, I wondered if Canada is descending slowly, imperceptibly, into an altogether new social structure. A Canada of onerous debt burdens, of social immobility. A stagnating Canada, where the only growth is the chimera of financial engineering. Is it possible that we're descending into a Canada of neo-feudalism?

Part I: No country for young wo/men

There was such a thing as the Canadian dream. It meant you could accomplish anything through hard work, your kids would be financially better off than you, and you could own a home. If the Canadian dream diverged from the myth-making of our southern neighbour, it was because our dream was built on quality healthcare for all, world-leading public education and most importantly, equality of opportunity.

Let's start with social mobility. A recent study used previously unavailable tax files to build a longitudinal view that stitched together parent-child incomes to see how they fare across generations. The results don't look good.

If you're in the bottom 40% of Canadians by income, then the odds that your child will make it, have been steadily declining. And it's not just that the opportunities are getting slimmer, there is also a non-linearity at play, which is a fancy way of saying that the decline is getting faster and steeper.

There are two factors here: income inequality and social mobility. According to research by Canadian economist, Miles Corak, higher inequality leads to lower social mobility. Corak's Great Gatsby Curve captures this relationship. It's a curve you don't want to be rising on - and that is precisely what's happening in Canada. The dots represent generational cohorts - notice how the millennial cohort has been shoved to the far right into a Canada of greater inequality and lower social mobility.

The reality is worse than the chart depicts. That's because the Great Gatsby Curve is based on income, not wealth. The fiscal and monetary policies of the past decade have led to a massive transfer of wealth from the young & poor to the old & rich. Unlike income, which is usually earned through productive work and can be taxed, in rent-seeking economies, wealth grows by itself mostly beyond the reach of the taxman. Wealth inequality is therefore much more skewed than income inequality.

In Canada, 60% of households own only 12% of the nation's wealth. This allocation, already meagre, is concentrated in real estate - an asset class that the younger generation is now priced out of unless aided by a rich parent.

Home prices in Canada are fundamentally disconnected from local incomes. Prices have been surging for two decades, but incomes have remained flat. Canadians don't earn more, but their homes keep on getting more expensive. Among the G7, a club of rich countries, Canada now has the highest home prices relative to incomes.

According to research by Generation Squeeze, a typical millennial today needs to save for 27 years to scrape together a 20% downpayment for an average home in Toronto. To put that in perspective, a 25-year-old starting their career would be 52 until they have enough money saved. Having rich parents helps, but only to a point. Even if your mom writes you a $100k cheque, you won't be able to afford the monthly carrying cost on the average home if you're a middle-income Canadian.

Canadians left out of the housing lottery are now losing hope. According to a 2021 survey by Manulife, 75% of Canadians who don't own homes want to buy one, but can't afford it.

As homes become unaffordable, Canadians struggle to find adequate shelter, with the most vulnerable pushed onto the streets. Given the difficulty of quantifying homelessness, researchers at Statistics Canada used Emergency Room admissions data for Ontario to map out the trends. If we take ER admissions of people experiencing homelessness as a proxy measure, then homelessness has more than doubled between 2010 to 2017.

These numbers, already alarming, also offer a glimpse into the latent inequities that plague Canada today. When sliced by age and gender, the rise in homelessness is primarily among the young, with working-age young men faring the worst.

So, if you're a young Canadian, your social mobility is eroding, you can't afford a home and you're at elevated risk of homelessness.

How do healthcare and education fare?

Healthcare

Despite a heroic effort by doctors and nurses on the front lines, healthcare in Canada is crumbling. Fraser Institute has been running a survey of treatment wait times for almost three decades, and the situation is deteriorating. Last year, Canadians had to wait 14 weeks on average to receive medically necessary treatment after the specialist consultation. When measured from the initial GP referral, the wait time for treatment is 25 weeks. Healthcare is universal, as long as you can endure months of pain.

It's not just specialist treatments where Canadian healthcare is lagging. According to Statistics Canada's 2019 Health Survey, 4.6M Canadians do not have a family doctor. The millions unable to get a family doctor have to navigate emergency departments and walk-in clinics, contending with protracted wait times and limited continuity of care.

Education

There is more to education than nudging students through an academic assembly line, welding on the skills they need to be economically productive. It's about nurturing curiosity and critical-thinking, empathy and social cohesion - competencies that can't be evaluated through standardized testing. There are, however, narrower skills that can be measured.

Canada participates in the Program for International Student Assessments (PISA), a triennial survey of high school students that is administered across the OECD. While Canada remains among the top nations, here again, there is a steady decline over the last two decades.

Given the systemic issues in our public education, it is only the dedication of school teachers that has prevented a steeper decline. And these educators are now burning out. According to a 2020 CBC survey of teachers in Ontario and the Maritimes, about one-third were considering retirement or leaving the profession. Educators have been warning about a crisis in public education caused by underfunding and managerialism, and the pandemic has only magnified these issues.

While there is scant evidence that private schools give better educational outcomes, parents with the financial means are preemptively turning to these programs anyway. In Ontario, the proportion of kids going to private schools went up by 34% from 2007 to 2019. Turns out that money can insulate your family from systemic decline.

To summarise: younger people have lower social mobility than their parents, have stagnating wages, can't find doctors and are at elevated risk of homelessness.

For this generation, Canada's decline is not hypothetical - it's their reality.

Part II: Crazy Rich Canadians

As I wait for the host to emerge through the oversized mahogany doors, I wonder if I'm at the right address. Perennial flowers carve circular colours into the front yard, their late summer wilt occupying more land than my North York apartment.

It has been a few minutes since I rang the bell. Sound must travel more slowly in the humid air of a Mississauga lakeshore mansion.

The doors swing open. As I'm led through the two-story atrium, past the formal reception room, and into the basement bar, my mind drifts... what does it take to earn real wealth in Canada?

Sheraz, the boomer who owns the place, is eager to answer. It may also be part of the answer to why Canada is in decline, bending towards an intergenerational negative sum game.

The trick to earning real wealth in Canada, it seems, is not to earn it in Canada at all. Sheraz, a Canadian citizen, has never worked here. He earned his money in a tax-free haven in the Middle East. In the early 2000s, he moved his wife and kids to Toronto, forming the model satellite family. The dad earning tax-free dollars, while the kids benefit from healthcare and education funded by Canadian taxpayers.

Most of the hard work in building his wealth, however, was done by the Bank of Canada.

Sheraz bought his custom-built, South Mississauga mansion with cash. He would've paid back then, what a 2-bedroom condo costs in Toronto now. In the intervening decade and a half, the price of that house tripled, fuelled by ultra-low interest rates, while our incomes stagnated. The BoC greasing the wheel of wealth creation - but primarily for the wealthy.

How did we get here, this point where Canada is no longer working for the working class?

I wish we knew the definitive answer, but we do know this much: the path winds through the treacherous terrain of foreign money, loose monetary policy, unfair taxation and exclusionary zoning.

Foreign Money

CD Howe, a Toronto-based think tank, estimates that between $40B to $100B of dirty money is washed through Canada every year. There is a global cottage industry promoting Canada as a no-questions-asked destination for money that needs a snow-wash. Canadian intelligence services rang the alarm in 1997, but the findings were politically inexpedient and the report was buried at the time. Twenty years of inaction made things worse. An independent inquiry into dirty money in British Columbia led by former RCMP Commissioner Peter German in 2017 concluded that: "…the infusion of (criminal) money into the B.C. economy from abroad led to a frenzy of buying, which in turn raised the assessed value of homes in large swaths of Greater Vancouver."

He named Greater Vancouver a "laundromat for foreign organized crime", and called money laundering in BC an "embarrassment" and a threat to society. In the two decades since the CSIS report, the threat to society is now nationwide.

While global crooks severely distort our home prices, there's an even larger force that Canadian homebuyers compete against: global wealth in search of safe returns. Josh Gordon from Simon Fraser University used newly released data to demonstrate the decoupling of home prices from local incomes. In areas with high foreign ownership such as West Vancouver (BC) or Richmond Hill (ON), there is an extreme divergence between the price of homes and incomes. This difference is explained by foreign money funnelled into Canada through proxies and satellite families. Our meagre after-tax incomes are no match against wealth earned in tax-free havens.

We pay the taxes, they get the homes.

Unfair Taxation

"Are you going after the guy with the two-car garage and the Peloton?" said Jagmeet Singh recounting a question during his CBC interview. "No," he asserted, "I'm going after the super-rich." And, it would seem, wage earners.

His friend with the double garage home would have made over $1M in tax-free capital gains over the past decade. If he lives in Toronto, then his property tax would be a mere 0.3% annually. And yet, the federal NDP gives him a free ride while increasing the tax burden on people earning over $200k. Hard work is taxed, while unearned wealth is protected. Even after doing everything right in life, the right grades, the right university degree, the right job - younger Canadians, including those in the top 2% of the income bracket can't afford good homes because our tax policy keeps homes inflated while penalizing hard work.

Property taxes rates across Canada have been trending down for two decades. The most expensive housing markets, Toronto and Vancouver for example, have among the lowest tax rates in North America. Keeping property taxes this low is highly regressive, but not in a way most people realize.

Much of the development in cities is funded by provincial and federal transfers (read: income taxes), however, the key financial beneficiaries of these developments are property owners. When a new LRT gets built, the land values go up, landlords extract higher rents from tenants - but their tax rate goes down. Younger Canadians, no longer able to afford homes, are in effect paying for developments that enrich property owners. Low property taxes are a transfer of wealth from the young to the property-owning class, hardening socio-economic divides and diminishing economic dynamism.

Exclusionary Zoning

Historian Anthony Sutcliffe suggested that zoning originated not only to promote safer, healthier cities but also to "keep the poor in their place." That was true of Toronto and Vancouver in the early 20th century - and it's true of these cities today.

In Vancouver, 81% of residential land is dedicated to detached and semi-detached homes. At an average price of $2M, the income you'd need to afford a detached home is so stratospheric that Statistics Canada doesn't even capture that income percentile. The semi-detached, though, can be yours if your annual income is over $250k.

According to Statcan, that's the threshold for the top 1% of income earners in Vancouver.

So, 81% of residential land in Vancouver is zoned so it can only be accessed by the top 1%.

Toronto is in a similar situation. The sea of yellow in Toronto's zoning map is mostly million-dollar detached homes. Poor people (that is the 99%) can live elsewhere - like basements apartments, micro-condos or bedroom communities far from the city.

This economic segregation has a name, it's called exclusionary zoning - and it is enforced by municipal politicians.

City councillors primarily safeguard the interests of property owners, who tend to be older and wealthier. They are also more likely to vote in municipal elections. Their interest is to protect inflated property values by restricting the supply of new homes - and councillors are happy to do their bidding, often under the guise of maintaining "neighbourhood character."

The city mayor and councillors keep prices unaffordable through a tangle of incoherent policies. First, they limit the land for new development through intensification targets meant to safeguard the greenbelt and reduce emissions. Good policy - but it goes downhill from here, because the city then passes the financial burden of intensification onto aspiring homeowners, not established ones who won the housing bonanza.

The city subsidies inefficient land use by keeping property taxes low on homes that sit on under-utilized lots, then they make it harder to add density due to misaligned incentives, and finally, they pile on exorbitant city development charges on new construction - costs that are eventually passed on to buyers.

This pattern repeats across major cities in Canada, resulting in a nationwide housing crisis. CMHC estimates that an additional 3.5 Million homes need to be built by 2030 to address the housing shortage, over a third of which are required in Ontario alone.

In the meanwhile, vacancy rates in Toronto are at the near historic low of 1.4%, rents have soared 20% YoY, newcomers struggle to find shelter - and city Councillors like Jaye Robinson continue to deny the housing crisis exists.

Monetary policy

"The world has largely exhausted the scope for central bank improvisation as a growth strategy" - Larry Summers, former US Treasury Secretary

Central banks across the developed world started an experiment in 2009. The 3 decades prior had been a good time. Regulations lax, money free-flowing. Then, as if without warning, organs started to fail and the lifeblood running through the veins of global finance dried to a trickle. While the good times were only for the bros of high finance, the misery of systemic failure was for the masses. The grand experiment then was to conjure up an unprecedented amount of money, pump that into the pallid finance system - and hope for the best.

While the Bank of Canada did not engage in quantitative easing during the global financial crisis, it still cut interest rates to near zero and injected billions into the banking system, primarily by purchasing mortgage bonds. The experiment seemed to work. After a brief hiccup, fondly referred to as the Great Recession, the economy started to click back. But the easy conditions created by the central bank were like crack cocaine to markets and the government. The highs euphoric and the addiction immediate.

For the government, monetary policy became a cure-all. From inequality to climate change - there was no economic ailment that easy money couldn't fix. By deflecting responsibility to the central bank, the federal government could coast on a rising tide of asset values. Surging house prices and the booming stock market, however, obscured an ugly truth: the government had mortgaged our long-term well-being for instant gratification at the national scale.

The relationship between easy money and asset price inflation is common knowledge among economists. A 2004 study by the Bank of Canada cautions that "a long list of empirical studies have found a correlation between excessive credit growth and asset-price bubbles." That's banker-speak for: if you keep interest rates low (for too long), bad things (can) happen.

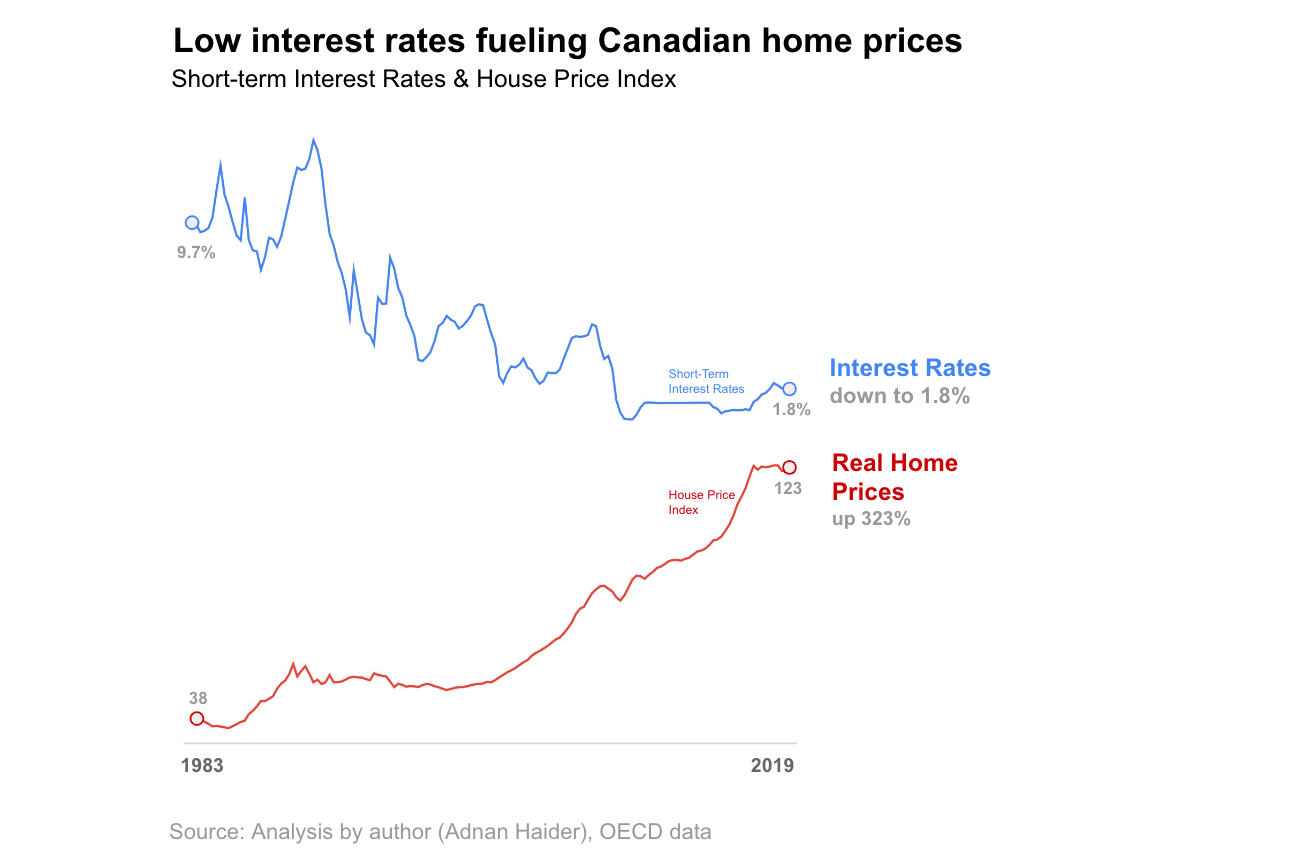

That's what we see in the data. From 1983 to 2019, the average Canadian house price shot up 323% in real terms, while interest rates trended down. The credit growth spurred by declining interest rates padded the paper wealth of boomer homeowners by arbitraging the prosperity of subsequent generations.

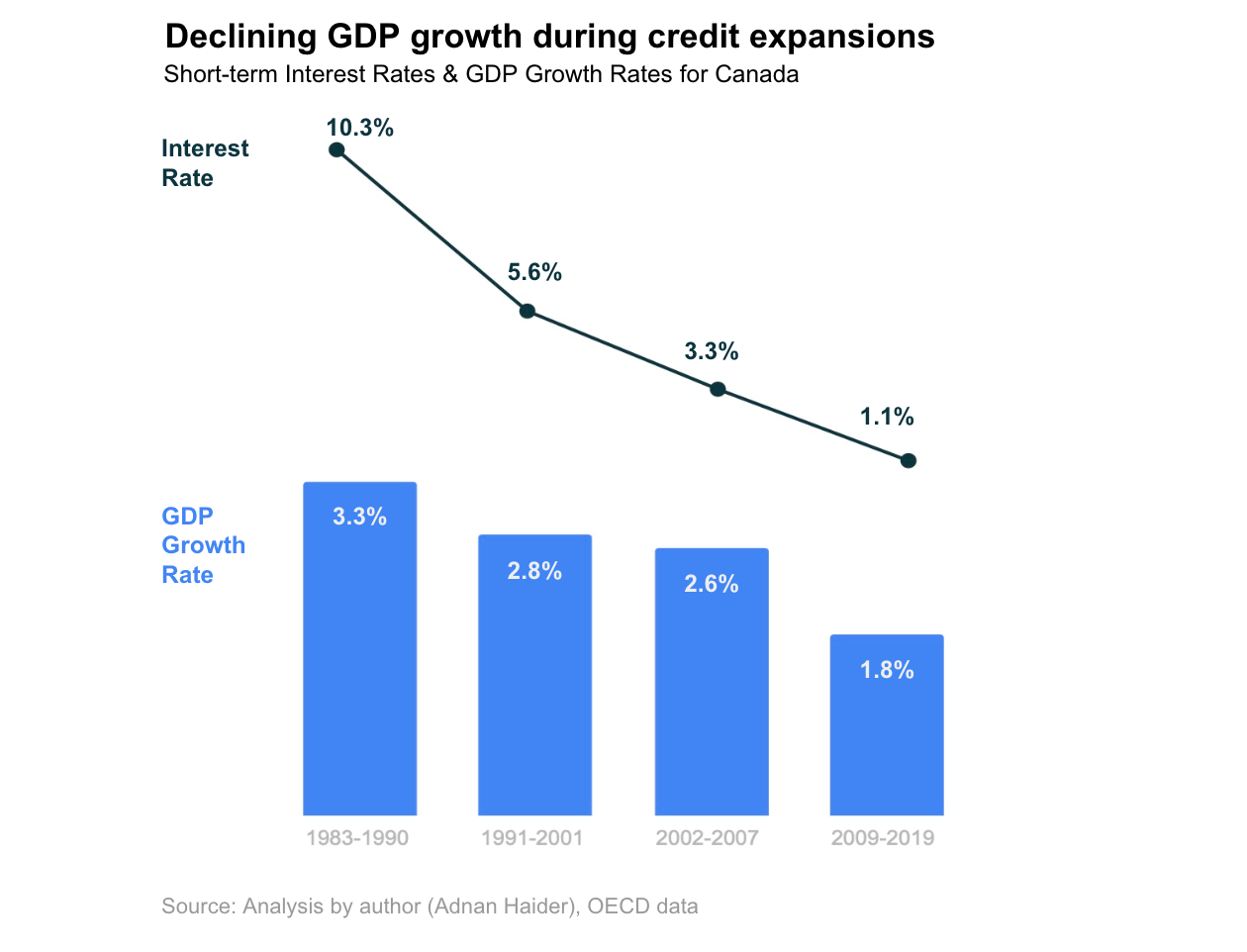

The theory goes that lowering the cost of borrowing encourages business investment, which in turn drives productivity improvements. Reducing the interest rate, therefore, is meant to trigger economic growth. But that growth didn't come. The Bank of Canada has cut interest rates lower in every expansionary cycle only to see ever-diminishing GDP growth rates.

The real failure of persistently low interest rates is not just that two generations are now priced out of homeownership, it's that it did not even lead to sustained economic growth.

In tracing the arc of our diminishing prosperity, we've encountered housing at every vertex. Here's why: Real estate may be at the heart of our economic malaise due to an obscure concept called "allocative effects."

Canadian housing is propped up by three levels of government, backstopped by a Crown corporation, and inflated through the liquidity infused by a G7 central bank. It almost gives the appearance of a risk-free asset, one with exponential returns and virtually no downside. When such a magical asset appears, it diverts investment from productive sectors. Business investment shrinks, households get weighed by debt and labour mobility decreases.

A paper published by CD Howe, a Canadian think tank, shows that business investment in Canada is lagging behind the US and OECD, a group of rich countries. The authors note that "business investment per available worker in Canada slipped badly after 2014" and warn that this is a "harbinger of weak productivity growth in the future." Productivity growth that we need for our incomes to go up and our public services to get funded.

According to a long-run economic forecast from OECD researchers, in the absence of any policy interventions, Canada's GDP growth per capita is expected to stagnate for the next 4 decades. In fact, Canada ranks at the bottom of all advanced economies. An infant born today will grow up in a Canada of stagnating prospects. Even as she's approaching middle age, her quality of life will be scarcely better than her parents, her station in life predetermined by the lottery of birth.

But this doesn't have to be our destiny.

Part III: The Long Game

"As a leader, one must sometimes take actions that are unpopular, or whose results will not be known for years to come." - Nelson Mandela

"There is always an easy solution to every human problem—neat, plausible and wrong," said American satirist HL Menken. For the Canadian government, the solution seems to be to throw money at the problem, like trying to extinguish a chemical fire by spraying gasoline.

Throwing money at the problem is easy, but structural reform is hard - and unpopular. It's time we do the hard stuff.

Structural reform doesn't mean austerity or a poorly conceived debt ceiling. It's about investing in our growth and it must start by fixing the most glaring misallocation of money, talent and opportunity in modern Canadian history: real estate.

As rates rise and real estate deflates, it may be tempting to sit back, and hope that Canada's torrid affair with real estate cools off. That would be a mistake. It will take more than a few rate hikes to unwind two decades of bad policy.

Reform taxation: Bring in Land Value Tax

Canada's housing crisis is a creature of fiscal and monetary policy. Bank of Canada's mandate is to manage Consumer Price Inflation (CPI), but the CPI does not include home prices. It's not the BoC's job to deflate housing bubbles. That responsibility lies with the Department of Finance - a department that hasn't had a dedicated minister for two years.

Monetary policy is too blunt to precisely target home price inflation. That's why unearned, and often speculative gains need to be addressed through fiscal policy. Enter, Land Value Tax.

The Land Value Tax (LVT) was conceived by Henry George, a 19th-century American economist. The concept is simple. Land ownership creates no economic value. Investors simply buy up land, wait for prices to go up and extract rent in the interim. That's great if you're the idle rich, not great if you work for a living.

The Land Value Tax levels the playing field. Since it's applied to land only, it encourages land owners to build more homes on the same lot. Since the tax is a fixed percent, as the land value goes up or down, so does the tax amount paid, dampening the boom-bust cycles.

Wealthy homeowners who often pay negligible income tax can no longer avoid taxes as the tax is levied on land, a fixed asset. Similarly, developers squatting on land waiting for values to appreciate need to either build or sell. Simply sitting on the land becomes unprofitable.

This tax reduces wealth inequality, makes homes affordable, encourages housing supply and contains urban sprawl. The tax collected can be used to build public housing - or as Henry George proposed, returned to citizens as universal basic income.

The Land Value Tax is one of the few things progressives and conservatives seem to agree on. Winston Churchill rebuked the land monopolist, saying that "he renders no service to the community, he contributes nothing to the general welfare…" and advocated a levy to tax away unearned increments in land value. Milton Friedman, a free market ideologue, endorsed the tax, calling it "the least bad tax." That's high praise coming from Friedman. Jeremy Corbyn, former leader of the UK's Labour Party included the tax in his manifesto to address Britain's housing crisis.

It is time for Canada to stop penalizing hard work, and instead raise money by taxing unproductive and unearned housing windfalls.

Redirect Foreign Capital

Earlier this year, the Ford government in Ontario appeared to hike taxes on foreign homebuyers, declaring that they're going after "…foreign speculators looking to turn a quick profit." At around the same time, Federal Liberals pledged to temporarily ban foreign ownership Canada-wide.

It was election time, and these announcements were perfectly calibrated to give the appearance of change while changing nothing at all. Riddled with loopholes, these policies were designed for easy circumvention. But more importantly, it was a textbook case of misdirection. The provincial and federal governments picked an easy target - the foreign buyer - hoping Canadians won't notice that the real blame lay elsewhere.

The problem was never foreign buyers, but foreign capital - money earned abroad and funnelled to Canada through satellite families and proxies. Homes in Canada should be for people who contribute to society and pay income taxes, not rent seekers who exploit permissive immigration policies to park their money and families here.

In 2018, a group of economists in BC proposed a research-backed mechanism to counteract the pernicious impact of foreign capital on housing affordability in Metro Vancouver. The proposal is simple: A 1.5% tax on assessed value that is offset against income taxes. If you own a million-dollar home, that's a $15k levy - but if you've paid that much in income taxes, then you don't pay a dime extra. There are also exemptions for seniors and those with a history of income tax contributions. All the money collected is paid back to tax residents, in effect lowering income taxes.

This tax only targets free-rider households who live in expensive homes and make no contributions to our society. They need to pay up - and this proposal needs to go nationwide.

Abolish exclusionary zoning

The city of Toronto recently published an official plan that "articulates a vision for our future." The plan starts by questioning the kind of city Toronto will be in the 21st century. You don't need to read past the first page to know the answer: a segregated one.

Toronto's city councillors, who presided over the development of the official plan, want you to know that 75% of the land, primarily detached homes for the rich and their heirs, is "not expected to accommodate much growth." The character of these neighbourhoods must be maintained. Much of the future growth, therefore, will be forced into just 25% of the land.

The young, the newcomers, the unrich risk being relegated to dense ghettos of the future - a service class to wealthy homeowners in their "established" neighbourhoods.

This wouldn't be so bad if the most accomplished amongst us - say an engineer or a school principal - could afford those homes. But no, constrained supply ensures that the privilege of a spacious home is only for the boomer, the foreign millionaire or the born-rich.

Toronto and Vancouver are the economic engines of Canada. Our prosperity depends on these cities, but our future is held captive by NIMBY councillors elected in low-turnout local elections to preserve the status quo. If the city is a creature of the province, then provincial intervention is long overdue.

While giving more powers to the mayor is a welcome step, it's not enough. If the city is unwilling, then the province needs to enforce planning reform and eliminate exclusionary zoning.

We need more homes and more neighbours.

Rationalise immigration

Canada will accept 431,645 permanent residents this year.

The federal announcement for these “bold new immigration targets” emphasised that they will offset an ageing population and “support a strong economy into the future.” But what if this economic rationale doesn’t stack up?

There is a policy dogma in Canada that pushes for raising immigration levels. In fact, there is a high profile think tank, called the Century Initiative, founded specifically to lobby for growing Canada’s population to 100 million by the turn of this century.

For the government, immigration is the easiest way to pump up the economy. More people means more demand for goods and services, translating to higher GDP. That new immigrants need housing, healthcare, and good jobs is an afterthought. Taken to the extreme, this disadvantages Canadians, as well as the recently arrived.

Immigration is not a simple utilitarian function, where more is always better. While high immigration levels are beneficial to mortgage providers and real estate investors it can also diminish the living standards of middle income Canadians.

For a country with the highest immigration rates globally, there is little Canadian research on the per capita GDP impact of immigration. The research that exists paints a mixed picture and is plagued by methodological flaws, however, a US-based study by Ethan Lewis at Dartmouth University may hold the key to whether high immigration levels in Canada are depressing middle-income wages.

Lewis found that production plants in US cities that have lots of low-wage immigrant labour invested less in automation than cities with lower immigration. Given the supply of cheap labour, businesses just didn’t need to invest in productivity improvements. This eventually led to lower productivity, and lower wages.

There are eerie parallels here. While the majority of Canadian immigrants are skilled, we know that many end up in low-wage jobs. We also know that Canadian business investment is falling behind. Could the two be related?

We can see a trend in the economic data. The median income for the cohort aged 25-34 has declined by 7% from 1976 to 2019. Let that sink in - the typical GenY&Z earns less than their parents did when they were the same age. And housing was affordable back then so the real decline in living standards is much steeper. There are many contributing factors here, but it’s possible that stagnating wages and high immigration levels are more strongly correlated than politicians let on.

While politicians focus on top-line GDP growth, the metric that matters for common prosperity is GDP per capita. Here again, the picture looks mixed depending on how it’s measured. In US dollar terms, our GDP per capita declined by 2% from 2010-2019. This is in stark contrast to the US, where per capita GDP went up by 31% in the same period.

There is ample evidence that high-skilled immigration enriches Canada. Immigrants bring inventiveness, culture and dynamism - and Canada should sustain significant immigration levels. We have a moral obligation to welcome refugees and an economic imperative to attract the top global talent - but we need to align our immigration targets with housing supply, healthcare capacity and economic opportunity.

In a wide-ranging essay on shaping policy to benefit Canada’s middle-class, Don Wright, the retired Head of BC Public Services, concluded that we need to “shift away from immigration policy that is focused merely on increasing GDP to one focused on increasing GDP per capita.”

That’s sound advice. The goal of our immigration policy should be to elevate living standards for middle class Canadians - and not merely to inflate the housing market national ego.

The case for optimism

We need a policy response that places our long-term interests above election cycles. Yes, that's getting harder as US-style polarisation permeates into our politics, but there is reason for optimism.

While the politician's impulse is to say what is expedient to get elected, the younger generation cares about the long-term - and they're now mobilizing to hold politicians accountable. This grass-roots mobilization crosses partisan lines, it's reshaping policy discourse - and in time will reshape election results.

Take, for example, More Neighbours, a pro-housing movement that is fighting against the injustices of bad housing policy. Or Generation Squeeze, a non-profit that is pushing for intergenerational fairness through research-backed advocacy. Or Better Dwelling, an independent publication drawing attention to how monetary policy has fueled inequality. The list goes on but they share a common theme: a concerted push to change the status quo.

Politicians are starting to listen. John Tory, running for re-election as Toronto's mayor, is campaigning on zoning reform. After years of delay, the federal government is bringing in a beneficial ownership registry to make money laundering harder. The NDP government in British Columbia has cracked down on money laundering in real estate and is bringing in legislation to build more homes.

And of course, Pierre Poilievre has made the housing and cost of living crisis central to his Conservative leadership campaign.

There is a swelling tide of resentment in Canada. Our response to it today will shape the country we become. We can see the contours of a possible future in the generosity of front-line healthcare workers who risked their own lives to keep us safe. But we can also see the outlines of a darker future in the Freedom Convoy - with their exclusionary freedom. As politicians animate these groups and their resentments for marginal electoral gains, perhaps they should remember that freedom need not be exclusionary.

There is a call to freedom that can unify the left and the right, the worker and the capitalist, the trucker and the cyclist: freedom from rent.

Now that's a freedom worth fighting for.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Mehryar and Maryam, thanks for your critical feedback and encouragement.

NOTES & REFERENCES

Corrections

- The census referred to in the introductory section is 2016 (not 2019)

Part I: No country for young wo/men

- Marie Connolly, Catherine Haeck and David Lapierre (2021). Trends in Intergenerational Income Mobility and Income Inequality in Canada. Statistics Canada.

- Paul Kershaw, Andrea Long (2022). Ontario just suffered the worst erosion of housing affordability in the last half century: Implications for the Ontario election. Generation Squeeze.

- Manulife Survey (2021). Housing in crisis: 3 in 4 Canadians who want a house, can’t afford one. Manulife Bank of Canada.

- Stephenson Strobel, Ivana Burcul, Jia Hong Dai, Zechen Ma, Shaila Jamani, and Rahat Hossain (2021). Characterizing people experiencing homelessness and trends in homelessness using population-level emergency department visit data in Ontario, Canada. Statistics Canada.

- Mackenzie Moir and Bacchus Barua (2021). Waiting Your Turn Wait Times for Health Care in Canada. Fraser Institute.

- Canadian Community Health Survey (2020). Primary health care providers, 2019. Statistics Canada.

- F. Avvisati, A. Echazarra, P. Givord and M. Schwabe (2019). Canada - Country Note - PISA 2018 Results. Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), OECD.

- Elementary-Secondary Education Survey (2021). Number of students in elementary and secondary schools, by school type and program type. Statistics Canada.

Part II: Crazy Rich Canadians

- Kevin Comeau (2019). Why We Fail to Catch Money Launderers 99.9 percent of the Time. CD Howe.

- Peter M. German (2019). DIRTY MONEY – PART 2 Turning the Tide - An Independent Review of Money Laundering in B.C. Real Estate, Luxury Vehicle Sales & Horse Racing.

- JOSHUA C . GORDON (2020). Reconnecting the Housing Market to the Labour Market: Foreign Ownership and Housing Affordability in Urban Canada. Canadian Public Policy.

- The National | Jagmeet Singh (2022). CBC News. (Skip to 40m)

- Canadian property tax rate Benchmark Report (2021). Altus Group.

- Citywide Zoning By-Law (2017). Toronto City Planning.

- Jaye Robinson denies the housing crisis (2022)

- Canada’s Housing Supply Shortages: Estimating what is needed to solve Canada’s housing affordability crisis by 2030 (2022). CMHC.

- GTA RENTS REACH NEW HIGH IN Q2 AS VACANCY RATE FALLS (2022), Urbanation.

- Thomas M. Hoenig (2017). The Long-Run Imperatives of Monetary Policy and Macroprudential Supervision. Cato Journal. (Note: The figure Declining GDP during credit expansions is based on this journal. I used the same periods of credit expansion since Canadian and US monetary policies are typically quite aligned, and the figure above is plotted with Canadian GDP data from the OECD.)

- William B. P. Robson and Miles Wu (2021). Declining Vital Signs: Canada’s Investment Crisis. CD Howe.

Part III: The Long Game

- Lars Doucet (2021). Book Review: Progress And Poverty. Astral Codex Ten. (Note: Excellent resource to understand Land Value Tax).

- Official Plans Chapter 1-5 (2022). City of Toronto.

- Don Wright (2021). Rhetoric vs. Results: Shaping Policy to Benefit Canada’s Middle Class. Public Policy Forum.

- Garnett Picot (2013). Economic and social objectives of immigration: The evidence that informs immigration levels and education mix. Research & Evaluation, Citizenship & Immigration Canada.

- By "Freedom from rent", I'm referring to freedom from rent-seeking. The point is not that everyone should own homes, it's that whether one chooses to buy or rent, the price should be reasonable.